S'EXPRESS: GAME CHANGER

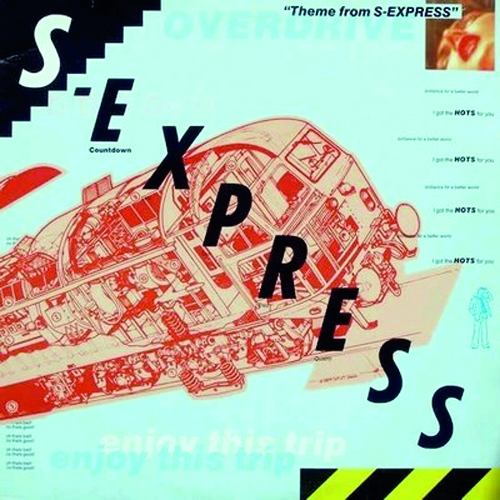

S'Express 'Theme From S'Express' (Rhythm King)

Mark Moore grew up in London and got into music at a young age. After his mother, who uprooted from South Korea after the Korean War, divorced his father, he spent some time in care before becoming a punk rocker.

He started collecting records, fell in with the Blitz crowd — the iconic New Romantic club run by Rusty Egan and the late Steve Strange — and then started DJing himself in 1983 at the Mud Club, run by notorious club-land entrepreneur Philip Salon, in Leicester Square.

Along with flamboyant Blitz 'face' Tasty Tim, Mark would play alternative electronic records — “Yello, Dead Or Alive before they had their big hits, the Misty Circles, things like that” — as well as “glam rock, schoolboy disco, a bit of hi-NRG like Bobby O, and stuff to stop people posing in the club.

The 'Rupert the Bear Theme', show tunes, Julie Andrews 'Lonely Goat-Herd' was always a floor-filler — ha ha ha! We thought posing was boring — we'd been through the Blitz and it was 1983, time to get out of that mindset.”

His DJ career took off. He started playing the Wag Club and upstairs at gay club Heaven, and when Tim and Mark got promoted to the main floor at Heaven they had to stop playing the silly stuff. “You had to be more serious, it was the main floor, it was proper,” he says.

Records by New Order and the Pet Shop Boys would be mixed in with tracks by electro pioneer Alexander Robotnick, German new wave band Les Liaisons Dangereuses, Yello's 'Vicious Games' and alt.stuff like that.

“We'd go religiously to places like Bluebird and Groove, get the new imports every week,” Mark recalls when DJ Mag visits him at home in Dalston one afternoon. “Everything was so mixed up then — we thought we were buying electro records, especially the Detroit stuff, like stuff on Metroplex, we thought 'Oh, this is like electro'. The housey stuff we thought was just badly produced Italo stuff.”

He soon realised that something was going on in Chicago as yet another import arrived on a Chicago label, and started becoming a bit of a house music evangelist. “Yeah, a fascist!” he chuckles. “I did a night at the Fridge, and I said I was just gonna play a whole night of house music.

I put a sign on the Fridge door saying, 'We play house music – do not come in if you do not like house music!' I just thought it was such amazing music. Other DJs did fit in the occasional house record, but it was just paying lip-service really. I just thought 'God, there's so many good things which people aren't concentrating on'.”

Becoming one of the UK's first house DJs, he influenced many who would follow in his wake. “Paul Oakenfold would come to Heaven, Danny Rampling would come to Heaven, Pete Tong would come to Heaven on the Pyramid night where it was me, Eddie Richards and Colin Faver playing,” Mark recalls.

“Paul Oakenfold was working for a promotions company called Rush Release, so he'd come down with loads of records — not his at that time. Once they started doing clubs, Danny got me to play Shoom pretty much after it started, Paul got me to play Spectrum, it was a tight-knit family thing. We were all going to each other's parties and it grew very organically — especially Shoom.”

At the time Mark lived opposite the Mute Records office on the Harrow Road. “Rhythm King had opened up in the Mute offices — I'd go and hang out there, nick import records that they'd be sent and play stuff in there,” he tells.

“I started taking them records and saying, 'Why don't you sign this?' and I took them things like Beatmasters and the Cookie Crew's first record [and proto hip-house joint] 'Rok Da House', which Tim Westwood gave me on acetate.

He said, 'Oh Mark, I can't play this to my crowd, but your crowd will love this', and he was right. So Rhythm King had a hit with that, and I also brought them Baby Ford, Renegade Soundwave, but before that the first hit I got them was Taffy 'I Love My Radio' — a cheesy Italo disco thing, that was their first hit.

It was fun times in those days, you didn't really expect anything — I never asked for any money or anything, but then they did give me a cheque.”

The Rhythm King people asked if there was anything else they could do for their unofficial A&R, and Mark said that he'd like them to put him in a studio. He met up with studio producer Pascal Gabriel and, armed with a rough demo made on a cassette machine consisting of loads of choice samples, set about making some tracks of his own. “I did 'Theme From S'Express' and the B-side 'The Trip', then 'Superfly Guy' and all the B-sides,” Mark recalls.

On Wikipedia there is a list of tracks that 'Theme' samples. DJ Mag starts reading them out to Mark — TZ 'I Got The Hots For You', Debbie Harry, Gil Scott Heron, Rose Royce, the Peech Boys, Gene Roddenberry 'The Star Trek Dream', Karen Finley 'Tales of Taboo'... “Karen Finlay was this amazing performance artist, we went to see her at the ICA and she was stuffing yams up her private parts!” he laughs.

“In the name of art. And she did these amazing rants — her bit is 'You drop that ghettoblaster' and also 'Suck me off, suck me off, suck me off' on the twelve-inch, not on the radio edit. It was produced by Mark Kamins from Danceteria, who discovered Madonna.”

“Did I sample all those records? I might've done — ha ha. The label cleared them all, in those days people didn't really know what sampling was, so they got a request and usually just agreed. It didn't take that long, people were generally just a bit bemused when you contacted them about it and offered them a couple of hundred dollars or whatever it was.”

Mark then explains that it probably took two or three days to make 'Theme' from start to finish, using an Akai S900 sampler, Cubase, some synths that were lying around the studio, and sampling the noise from a hairspray for a hi-hat.

“I was speaking to Paul Morley and he said 'New Order did that on 'She's Lost Control' and I was like, 'I don't believe that, I think you've rewritten that after the fact'. The film 24-Hour Party People actually has them in there with the hairspray, but I don't think that ever happened.”

At that point, 1987-8, disco was still considered naff. “Disco sucked from 1979 onwards, in the eyes of rock people and I guess everyone,” Mark concurs. “So why did I want to bring disco back? Cos it's so good! Cos it's so not naff!

I always loved disco, even as a punk rocker hiding my disco records, I loved disco. I wanted to make sure the S'Express record didn't sound like anything else — I didn't want it to be a copy of a Detroit record or whatever. All my influences were thrown in, especially the punk influences, and if you were a proper punk rocker you didn't try to sound like someone else, you tried to do your own thing.”

He talks about how he was hugely influenced by hip-hop, played a lot of Def Jam stuff at the Mud Club, and loved the whole idea of looping breakbeats. “I thought I'd apply that to disco,” he says. “Looping disco, instead of looping James Brown.

So there was a lot of Double Dee & Steinski influence on that, 'Lessons 1, 2 & 3' — those famous hip-hop lessons — which they put on vinyl. A lot of the techniques of hip-hop were involved in that record. I wanted to make it more than the sum of its parts, so everything went into the pot.”

A cut & paste sampladelic triumph, at once campy and knowing, sexy and acidic, 'Theme' smashed into the UK pop charts purely on the strength of club play. “Radio 1 wouldn't play it, they said it was too weird, and Rhythm King said 'It's too weird for Radio 1, you have to do a radio mix that isn't so crazy-sounding',” remembers Mark.

“We were like 'No, we don't want to do a radio version', and they said we had to do it or it wasn't going to go on the radio. So we went in and did the worst seven-inch radio mix that we could do, and gave it to them. They said, 'This is terrible', and we said 'Yes, it is', so they didn't put it out. They kept the seven-inch as it was — and thank god we did.”

On the second week of release, 'Theme' shot up the charts and into the top five. “Radio 1 thought, 'We're gonna look like fucking idiots if we don't play it', so they played it and it went to No.1,” states Mark.

“Then it all went crazy. I became a pop star, without meaning to. I thought I was going to enjoy five years of being in a cult band, and then selling out at a later date — but suddenly I was a pop star, and I didn't really like it.”

He talks about his punk ideals, and how he and various other people around him who'd also got in the charts were quite blasé about the whole thing. “We all thought it was quite naff to be a pop star — but kinda loved it at the same time!” he says.

“It was one of those. We weren't unprofessional, cos we turned up and we did the photo sessions, the interviews, the TVs, the radios, we were always on time — maybe a little bit late — but we turned up.

But we were really unprofessional, cos I'd be in Smash Hits going, 'Ooh, I hate children buying my records!' and things like that. Rhythm King would be like, 'Why are you saying this?' It was really not thought-through properly.”

Mark recalls saying in an NME interview that anyone could join his band, and so loads of people would come up to him in clubs and end up in his videos. A young German woman called Billie Ray Martin was one of these, and Mark invited her to the studio the next day to sing on 'Hey Music Lover'.

She went on to appear on a few tracks on the debut S'Express album 'Original Soundtracks' and launch her own groovy-yet-detached dance project Electribe 101. “So it was weird, I had these meetings that were almost meant to be with certain people,” he recalls.

“I quite like the fact that people thought I had an open door in my band. I remember at one point Pete Tong saying to me, when he worked at ffrr doing A&R, that at one point every girl who came in with a demo claimed to have sung for S'Express — about a hundred of them!”

'Theme' effectively opened the doors for house music in mainland Europe, although Mark kept having to explain that 'Theme' wasn't a typical house record. “The band helped, to package and put on a TV show,” Mark reckons.

“I did the band as a post-modern exercise, it was like my art project, and also so that my friends could come with me and I wouldn't get bored.”

A singer called Sonique got involved for the second album, which also featured some drum programming by a young Carl Craig, before Mark got bored and finished doing S'Express. “I got sick of the whole circus,” he relays.

“It got to be that you'd record for a long period, then you'd have to do all that promotion and photo sessions and interviews, and it was this merry-go-round and I thought 'Oh my god, this is my life now'. I remembered how happy I was just being the DJ, so I thought 'Let's knock this on the head', and I went back to DJing.

I thought I could just blend into the background DJing, and that's when all this superstar DJ thing started blowing up and it was all 'Oh no, you've got to raise your profile, you can't just be in the background!' Just when I was trying to get away from it!”

He did the 'superstar DJ' thing for a few years before becoming sick of playing 'superclubs' like Gatecrasher and Cream. “I stopped doing those clubs and I started playing at the 333 club [in Shoreditch] playing the Human League and stuff like that — and then all that electroclash stuff started happening, and that was just incredible,” he zings. “Again it was like, 'That was good serendipity'.

Then Nag Nag Nag opened, and suddenly it went from being all about the club and the superclub and about the DJ to being about the audience again, which is how it was when I first started DJing — and how it should be. Suddenly these kids who were dressing up were the stars again, they were starting crazy electro bands — some were awful, some were brilliant, didn't matter.”

Mark is currently curating an S'Express remix album (more about that soon), and tells the story of how 'Theme' was supposed to be used by Danny Boyle at the 2012 Olympics opening ceremony as Team GB came out onto the track until a last minute publishing dispute scuppered it and they had to play the Chemical Brothers twice instead.

He still gets hassled to play 'Theme' when he DJs, he says, but is a bit sick of it — luckily he has some remixes to play out now. “Has it been a millstone? No, that record's been a good friend to me. I would never call it a millstone. It opened doors. It changed my life.”